Just you

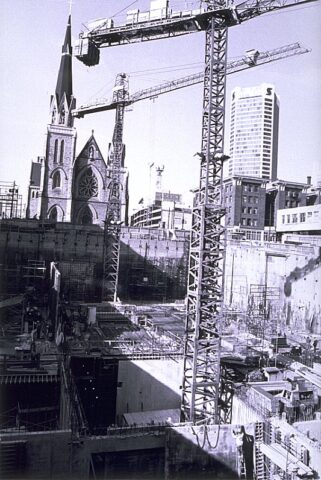

1972-1990

New Politics, Old Dream & The Roller Coaster Years

New Politics, Old Dream

In 1972, Dave Barrett’s New Democratic Party came to power, replacing W. A. C. Bennett’s Social Credit government. Although ideologically far apart from its predecessor, the new government shared with it the vision of BC Hydro as the central tool of provincial development. And develop it did. Unprecedented growth followed-in the number of bus routes, in the expansion of generating capacity, in staffing levels, and in spending.

Gerry Bramhill remembers the concerns he had about the growth.

The new government saw nothing but growth. Hydro almost had a free hand to do whatever they wanted to do. No matter what corner of this province you went to, there was something going on in Hydro. If you weren’t building, you were dismantling and replacing, or you were building up district crews. I couldn’t believe the bulletins we used to have in those periods of time for more manpower in the headquarters. Everybody was building empires.

In early 1971, I came in to the union office to start up a dispatching system. In those days, IBEW local 258 was clearing over a thousand members a year out of the hall. The work was so fantastic at that time-and keep in mind, too, that our only employer back then was BC Hydro. Right through to 1984, BC Hydro was the only collective agreement and the only membership we had.

We had some very active times, over a thousand people coming in and out of the hall for short-term construction and hydro systems. I brought in about 400 linemen from the United States during that time. We worked with Employment and Immigration Canada to sort out visas, and we shuttled them all through our Seattle local unions.

In 1975, Gerry became assistant business manager and made his first visit to the Mica construction project as a union representative. The experience both excited and disturbed him.

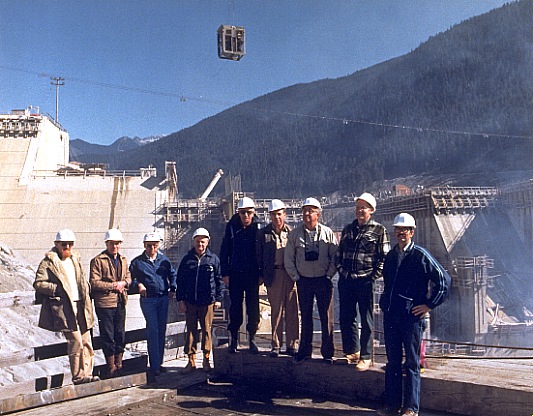

I took that old highway from Revelstoke, half gravel and God knows what else, to Mica Creek. It was an eye-opener for me to see what could be developed out of a river basin. It was at the height of construction and there were something like 2,000 employees in there at that time, between the contractors and BC Hydro. There was an old hotel, and you could see dollar bills pasted on every inch of the wall, with names on them. The workers themselves were just hyped right up. There was so much to do. They worked hard, but they didn’t really give a damn if that job lasted today or tomorrow, because they would just go somewhere else. The attitude was “Let’s make the bucks and get out of here.”

Boom times can be a negative thing in some ways. Hydro will tell you today that much of what they did during the 1970s could have been slowed down. The building of the 500-kV lines and all of those things could have been done over a longer period. They didn’t need them at the time; we were overbuilding and people knew that. I don’t know if it was politics or whether it was a spin-off of the Bennett dream of the Columbia River, but there was no stopping it.

Faced with a shortage of qualified linemen, Hydro started a dayschool in late 1974 at the company’s Gilmour Street training centre in Burnaby, complete with practice power poles and lines. Instructors for the school were Hydro journeymen linemen from districts around the province. Only half the students came from Hydro-the rest were from other industries that needed linemen, such as mines, mills, municipalities, and construction.

The early 1970s saw a recommitment by Hydro to building up its own construction forces to be able to take on any kind of project (other than dam construction, which was done by contractors). Ross Fitzgerald moved to the construction division from district management at that time and recalls with pride the quality of work the in-house crews produced. “We often did the work cheaper than the contractors-I think we became good, innovative construction managers.”

Wally Lyle heartily agrees. He was the manager of BC Hydro’s construction forces during this period and remembers it as a time when good teamwork produced excellent results.

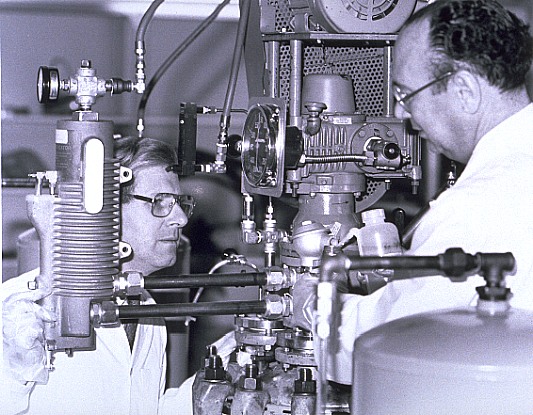

The new management at Hydro really gave us a green light to do the work in-house-and to do it right. I was able to hire new supervisors and new engineers to work on transmission, distribution, and substations, and civil-mechanical jobs. This was the time where we did lots of 500-kV work. We forged ahead and created new systems for costing and computer costing. We pioneered new equipment for 500 kV-remember, this was all new work which needed special equipment. We increased our fleet. I don’t think we really slowed down until the economic downturn in the early 1980s. We built the system, maybe overbuilt it.

There was a lot of brainpower behind the 500-kV system, not just the research behind it all but for applying the research and making it work. People like Reg Radelet, Bill Rea, Hoss Short, Don May, and Fred Bergman, who had good ideas for new equipment and techniques, which we then built in our shops and managed to create by purchasing the right tools. We used helicopters in ’60s. But it was in the ’70s that we did the real pioneering work with helicopters, to build those huge lines. Again, we developed special tools and techniques. We did things that a lot of people didn’t think were possible and those helicopter pilots were damned brave and were willing to try things, like stringing five miles of pea line. We had the big Sikorsky helicopters that could lift an entire tower and bring it into place. The crew on the ground would be there already. Everything was pre-measured by instrument; they built a foundation, and down came those towers. We put those things up in unbelievable terrain. And the good thing about using helicopters is that we didn’t have to build roads, which was better for the environment.

What this all involved was teamwork between management, purchasing, labour and the unions, and the supervisors and superintendents. Everyone. We really couldn’t have done it without the great tradespeople IBEW 258 sent up to us. We were busy all around the province-still moving diesels up North, doing new underwater cable work, building new substations with low profiles, and doing some excellent exploration and drilling. The beauty of being able to work in-house is that the guy who builds a tower or a substation can walk down the hall and talk to the guy who designed it. It is pretty efficient.

When I think about it now, they haven’t done 500-kV work for a long time. If there is a big storm that brings some of those towers down, I wonder where they’ll get the expertise and equipment to respond?

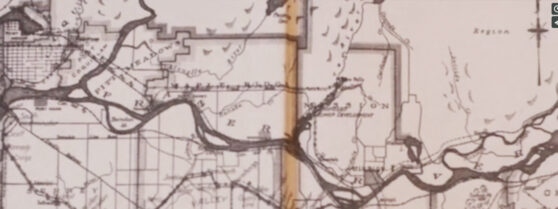

Reg Wesley, who was with Hydro from 1966 to 1995, is a member of the Haida First Nation from the village of Skidegate. He was doing labouring jobs for Hydro when he wasn’t working as a commercial fisherman. All the expansion gave him and other workers a chance to improve their skills and to advance. One of his early promotions came while he was working on the transmission line between Prince Rupert, Terrace, and Kitimat in 1966. His decision to upgrade would come in handy during the 1970s.

Bill Risk, who was the construction superintendent, came up and said, “Reg, we need a powderman.” I said, “I don’t know anything about being a powderman,” but he said, “Well, we have a guy here that can teach you, Mike Cupto. He can teach you for a couple of weeks. I know Barry Payton in Vancouver, who is the inspector, and I’ll set up the test. And we’ll pay your ticket down.”

I worked with Mike for a couple of weeks, went to Vancouver, passed the test, got my blasting ticket, and worked for several years doing blasting and supervising the general trades crews around Rupert, Kitimat, Bella Bella, Bella Coola, and Shearwater-all over that area. We’d fly in to most places. I’d take my powder in one plane and someone else would fly with the caps. We’d stay in a trailer and work whenever there was daylight for, say, two weeks at a time. A contractor would come in and do the grading.

Later on, Dennis Cross and Les Jensen encouraged me to go into line supervision. I had relieved a few times, but finally they said to apply for a supervisor’s job. I didn’t have Grade 12, but they said if I got it I’d have a job. I had gone to school in Port Alberni when I was 13 years old-they sent me to the residential school there, and I was short some credits for graduation. So, fine and dandy, I went back to school and I was 38 when I finished Grade 12. In fact, I graduated with a bunch of kids who had worked for my wife while she was in the catering business.

Well, then I applied for a job opening as a line supervisor in Dawson Creek. My wife and I went to Dawson Creek to look at housing. It was 40 below Fahrenheit when we got there, and she asked me what in the hell we were doing there. But when we woke up in the morning it was 10 above. We stayed for a week, found some housing, and I stayed there for three years.

The Roller Coaster Years

In the 1970’s and 1980’s, BC began to reap the benefits of huge investments made in the 1960’s. Yet, during this time, the company that had made so many of these investments went through some particularly painful changes. Unlike the post-war years and the decade following BC Hydro’s amalgamation, the way ahead was no longer one of continuous upward movement. The corporation was entering a new era, one of new politics, new social activism, and new expectations from ratepayers. And it was into a new scale of production. Just as its predecessors had gradually increased capacity in the early part of the century, Hydro was now well into the age of the gigawatt – a measure of energy equal to one million kilowatts.

These two decades also saw important changes in the way the company was managed. No longer did very powerful and very public chairmen like Dal Grauer, Gordon Shrum, and Hugh Keenleyside put their personal stamp on “eras” that defined the company. However, while there were no fewer than six chairmen at the helm between 1970 and 1990, each had a strong impact.

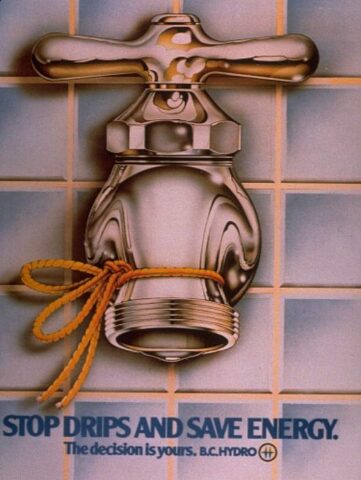

As this era began, there was a new approach to spending, expansion, and staffing that would affect the company a decade later. Many would benefit during these exciting years, and many would argue then (and later) that it was all too much, too quickly. Reorganizations, downsizing, and transfers and privatization of various parts of Hydro changed the shape of the company so fast that employees sometimes felt dizzy with the pace of change. Externally, global events such as the oil crisis, recessions, and increasing regulation made Hydro’s work ever more complex.

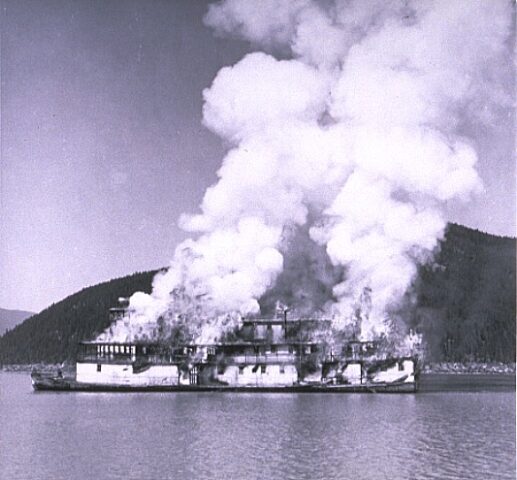

As this period ended, Hydro was a very different organization, one dedicated strictly to the generation and sale of power. The historic transit, freight, gas, and motor transportation businesses were all gone. Many of the venerable internal divisions-Home Service, Farm Service, lighting and heating sales, Industrial Development, and more-had been absorbed into the organization, their functions carried out in different ways or not at all. BC Electric, the BC Power Commission and BC Hydro had always been directly or indirectly involved in politics, and were certainly affected by them. But now, at times, the political and public scrutiny would seem particularly intense. Its achievements in the 1960’s and 1970’s put Hydro in demand, and it took on international contracts and offered consulting services around the world. Due to internal and external pressure, it had become an organization that was highly conscious of the natural environment.

Through the mid-1980’s and later, a great number of Hydro’s current Power Pioneers, many of whom were with the company for 30 or 40 years-sometimes longer-retired. They left their company in good shape, and in good hands.

The Silver Thaw Of ’72

The year 1972 blew in with one of the most devastating acts of nature Hydro had ever faced in the Lower Mainland. To the old-timers who had experienced the great storm of 1935, there were a lot of similarities. Both storms hit on almost the same date: January 21 in 1935 and January 20 in 1972. Bob Sharman was one of the many Hydro employees who pitched in to clean up the damage caused by the 1972 ice storm. Bob was already working with a line crew in Agassiz-the epicentre of the storm.

It started on a Wednesday night. The day before we had a slight bit of an ice storm over in Agassiz, and we’d been out on that. Then on the Wednesday night, half of the line crew went bowling-we had a bowling league on Wednesday nights. We came out of bowling at 9:00, and it was slippery, so we all decided the safest place to be was down at the Legion. After a couple of drinks, what happens but Carl Battell comes walking into the Legion looking for his line crew. We couldn’t get out of it, so we all went to work.

Out in the bush the old poplar trees were cracking off and snapping like sticks because they were frozen and loaded up with ice. You’d look across there, and they were just levelled, the whole field. We worked through the night doing repairs, 16 hours, and then went home to sleep.

It wasn’t that cold, actually, because an ice storm occurs at right about 32 degrees Fahrenheit. It has to come down as rain and freeze on contact. Normally, if they know there is a storm building up, they overload the transmission lines so that the wire will go up a few degrees above the environmental temperatures. They had ice storms in the Valley pretty near every year in a minor way. They might only last an hour or so. But this one had lasted for over 24 hours. My wife, Dorothy, and my daughter went out at eight in the morning with an umbrella up, waiting for the bus. It never showed up, so they came back in, but they couldn’t get the umbrella down because it had a sheet of ice on top.

Next day, Hydro sent up some more men to us from Surrey. The ice storm only affected Agassiz, Chilliwack, and not much in Abbotsford, because we had most of the Abbotsford crews up in Chilliwack. I made up a crew and we set out from Agassiz to Seabird Island, trying to make it up to Ruby Creek, because one of our poles had fallen across the CPR line there and they couldn’t run the trains. Then we heard that the 500-kV line from the Bennett Dam was out. They couldn’t figure out why or where, because it was still snowing and blowing and ice, and they couldn’t even fly in with a helicopter. We were driving along after dark, and just before we got to Seabird Island we couldn’t see any wire up above. And that was because it was down on the road-we were driving over top of it! So I radioed in and I said, “I think I may have found out your problem.” Every tower was down for five miles.

It’s hard to believe that those steel towers would crumple like that. They looked like somebody had taken a fist and just scrunched it up like tissue paper or something. A bunch of matchsticks.

Gerry Bramhill and his fellow line workers were also sent out that night. He remembers the difficult conditions on Seabird Island, where poles and transmission towers had come down.

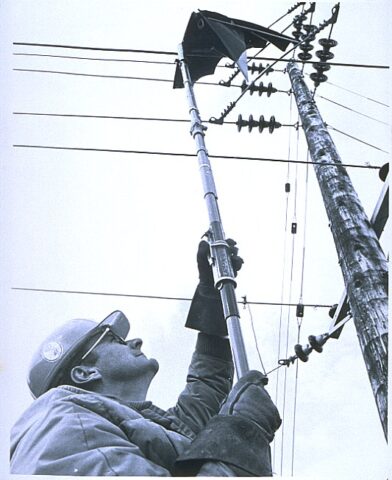

We were trying to climb poles and using chisels and small hammers to chop our way up. We had to chop the ice away so that we could get our spurs in to climb the poles. The ice was two or three inches thick. As you were going up the ice just kept coming-and it was pouring ice rain. We chopped our way up the pole and chopped the ice off to get back down.

To Warren Byrnell, who was working in power dispatch at the time, it was as if part of the system had disappeared-and Hydro had to find a way to keep the lights on.

Up in the Agassiz area, the big lines from the Peace River just evaporated from the system. The only high-voltage line to stay on the system was the 360-kV line from Bridge River to Rosedale and Rosedale to Ingledow Substation. They had an awful job to synchronize it back into the system, because it had never happened like that before. Duncan Stewart and I went in to work early for an afternoon shift-purely by accident-and didn’t leave until the next morning.

When you lose major transmission you have to start offloading customers. You start with businesses, because you don’t have the power to supply them and you can only get so much from Bonneville. Actually, what happens is you have to get them to start offloading, taking themselves off on an orderly basis. So we had to contact these big customers like Hooker Chemicals and ESCO and so on. The last to go are the residential.

Hydro’s Industrial Sales staff, including Jim Watts, Bill Dickinson, Bob Brassington, Walter Grey and George Barnett kept up daily contacts with the large industrial customers to keep them informed.

Hydro had been a member of the Western Systems Co-ordinating Council (WSCC) since 1967, which allowed BC and 14 states in the American West to help each other out in case of emergencies. Instead of the type of domino effect that had knocked out the entire eastern seaboard in 1965, power started flowing north from the US immediately. By Thursday evening, Hydro started bringing in crews from Vancouver Island and up country. Mike Morris was in Nanaimo at the time.

On Thursday nights we always went to the Quarterway Pub to cash our cheques. So we were drinking some beer and Dick Reay, who was the supervisor, came in and said, “You guys are going to Chilliwack.” We said, “Oh, get off it,” and he said, “You’re catching the 11:00 p.m. CPR ferry over there.” We still thought he was kidding, but we were on that ferry. They said it had to be bucket trucks, but we didn’t realize why until we got there. You couldn’t climb the poles, they were frozen so hard.

We went over with Chuck Preston, Bill Manson, Cliff Steadman, Paul Sheepwash, and Jack Weeks and stayed in the hotel on Young Road. We just about froze to death when we went in there, because there was no power. I remember Chuck Preston saying, “This is the first time I slept with my work socks and underwear and everything on.”

Matters were made worse when an avalanche knocked out a 500-kV transmission tower eight miles from Squamish. But by having the line crews work overtime, receiving surplus power from Alberta and neighbouring American utilities, and running the Burrard Thermal, Port Mann, and Georgia generating stations at full throttle, Hydro was able to avoid major brownouts or blackouts.

During the crisis, Hydro’s Information Services also worked overtime. Jim Sexton, Neil McKelvie, Trevor Collins, and Bill Chatterton all worked the phones to keep the media and the public well-informed. Meanwhile, metropolitan Vancouver and Fraser Valley customer service and trouble centre staff handled a deluge of calls.

The situation remained critical for a week, but the public and bulk customers alike responded by reducing their electricity use. Eight days after the storm, links with the Peace were partially restored. The crisis was over, and for several nights thereafter, the lights in the Hydro headquarters blazed out a pattern with a huge “THANKS” written across the top floors of the building.