Just you

1945-1962

Young Turks & Wily Veterans

Young Turks And Wily Veterans

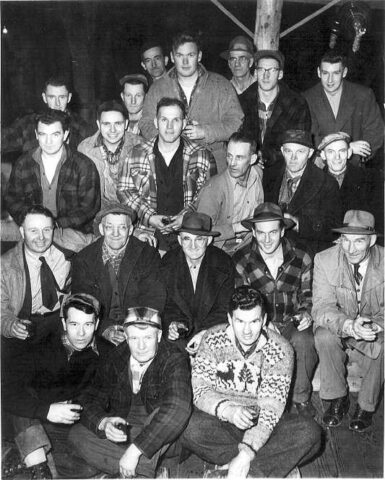

The early Power Commission years were characterized by a dynamic mix of youthful enthusiasm and “school-of-life” savvy among its employees. The employees included kids fresh out of high school or university; returning veterans ready to get back to work, raise families, and leave the horrors of war behind; and experienced power-utility workers “inherited” from other companies. The mix seemed right as everybody buckled down to get the job done.

Twenty-five-year-old Tom Farmer of New Brunswick started with the Power Commission in 1946, after serving with the RCAF, and retired 35 years later.

I put in some training time in Vancouver in the vocational shops and then got a job as an operator in Sechelt, where the diesel construction crew was installing an old diesel engine. And when I say old, I mean it was probably in the order of 40 or 50 years old. An older Atlas air blast. I doubt that too many other diesel people these days would know what an air blast unit would be. My job only lasted about a month there and then I was told to go up to Smithers. So I parked my wife in Vancouver in a room-all we had was a room-and headed up to Smithers.

The trip was very cold, dirty, and damp. You had to go all the way through to Jasper by rail, and then on up through Smithers. This was in November. Smithers is beautiful now, but it was quite a dirty little dump in those days.

We had a couple of very old diesels, and it was just a matter of changing one over to another smaller unit with the light load, and a larger unit for heavier loads. And then I was told to come down to Westbank, in the Okanagan. The job lasted some three years, so this time my wife could join me. We got settled in a con-verted garage. It consisted of two rooms, an outhouse, and a cold water tap, and that was all. After the first year down there, I was made chief operator. My salary jumped to $125 a month from $110. At that time it seemed wonderful.

Art Price was among the BCPC employees inherited from existing power companies. In 1945, he was a young diesel operator in Vanderhoof when he received a letter from the head office of his employer, the Columbia Power Company. It informed him that the company and its seven small power plants were being taken over in August and that all the employees would be kept on. The letter said, in part:

Personally, I think the men like yourself, who happen to be with us at this time of changeover, are rather fortunate. Government departments are generally easy and pleasant to work for. It is my guess that the Government will be at least as good a boss as the Columbia Power Company, and possibly a good deal better.

The work proved far from easy, but Art never regretted his decision to stay on, working for the Commission and then BC Hydro for 35 years.

When Russ Hamilton returned to West Canadian Hydro in Vernon (where he had started in 1933) after four years in the RCAF, he found that the small company was now part of the new Power Commission and that ambitious plans were afoot. He was asked to help start a meter shop that would serve the interior region. The Commission was responsible for improving the distribution of electricity throughout British Columbia and one of the ways it did this was to take over small utilities, many of which were in dire financial straits. Russ remembers what that meant to someone working in the field.

When we started the meter shop we had to deal with all sorts, including five-amp meters that could only operate a couple of lights in houses. All these new appliances were coming out that people wanted-ranges and electric heaters and so on-and all these small utilities were faced with the same thing: having to increase production. But they couldn’t afford it because they just couldn’t raise their rates.

I was quite familiar with the plant in Clinton, and in that operation no one could hook up a range because the plant didn’t have the capacity. To raise capacity, they were faced with a $50,000 investment, and no way could they could raise the money. Customers were already paying 15 or 20 cents a kilowatt hour. There was no way these companies could have survived.

At Burns Lake there was a diesel run by one fellow. He wanted to keep the plant, but sometimes he’d leave early and shut down at 10 o’clock-and the power was 25 cents a kilowatt hour!

Some employees were recruited straight out of university. The UBC 1946 class in electrical engineering produced eight graduates who became important Commission employees, including Don Wales, Steve Howlett, Norm Olsen, Larry Wight, Norm Latimer, Wilf Kenny, Walter Marks, and Wally Lyle.

Even before the class’s graduation, BCPC chairman Sam Weston had talked to the university’s combined engineering classes about the government’s plans for electrifying the province. Norm Olsen was 22 at the time and remembers how Weston caught the imagination of some of the class members.

He said he was looking for engineers who would be trained to manage this new utility. It was mostly made up of small, diesel-powered communities around the province, but he fascinated a group of us with the picture he painted of how exciting it would be and the tremendous opportunities. And he painted such an exciting picture of what was going to happen in the province of BC. Economic development would only be possible with electrical power, so you needed a public electrical utility. It was tremendously exciting and the best possible way one could spend one’s life.

At that time, BC Electric had one job they were offering and that was in their meter department and it didn’t interest me at all. One of my friends took that job in BC Electric and was hired at $150 a month. The Power Commission hired four mechanical and four electrical engineers at $100 a month. And no expenses.

Only one of the eight of us was married. Because we would be required to move around the province, and have to be willing to go anywhere and do anything that was requested of us, Weston said he expected us to stay single for five years. As it happened, I stayed single for three years.

Sam Weston always left a strong impression on people as he enthusiastically preached his personal philosophy about public service and public power-a philosophy that eventually became that of the whole organization. “Power according to Weston” was distilled into an epigram that he repeated at every opportunity and even had printed and handed out to his band of power zealots. Part of it read:

A utility is a thing with a heart beat-a steady beat of progress-brought about not by water and wire, penstocks and poles, turbines and transformers, but by all the people who put our resources and equipment to the benefit of all. Ours is a job of service; and the service we render is the lifeblood of the community we serve.

Norm Olsen recalls Sam Weston and his style with fondness.

Mr. Weston was a big man with a deep voice and a very imposing personality. He had cold, steely eyes and I found him very intimidating, but he had a tremendous ability to inspire you.

He had a practice of holding regular meetings with district managers because the district managers were the representatives of the Commission all around the province in very key positions. The towns were very small, like Alert Bay, but it was the beginning of the extension of public power, and public support for public power was essential. Weston recognized and promoted the importance of these district managers, so we had many meetings in head office with the commissioners. The chairman would meet with us lowly little guys and preach to us. And that’s what kept a lot of us going, that shot in the arm every now and again about the service we were providing to the community.

The commissioners started building up the staff from nothing. A lot of the staff were former military, so there were all kinds of captains and majors and so on around. But the corporation was very democratic. When we lowly district managers came to Victoria to meet with the commissioners, General Foster would host dinner in the Union Club or the golf club. You could speak to the chairman and have a cup of coffee with him and play poker with him-we used to play penny-ante poker with the chairman of the board. He lost all the time, too!

Tom Farmer was also a district manager, and he remembers Weston’s little “talks” at the meetings in Victoria.

Oh, he’d give us a wonderful, fiery speech every year. And then he’d send us on our way back to the district offices, feeling that we could whip our weight in wildcats.

In such a small organization, Weston and his fellow commissioners knew virtually all the employees. Jerry Wills started working with West Canadian Power in 1941 and retired from BC Hydro in 1978. As a union representative during his BC Power Commission years, Jerry occasionally went to Victoria for bargaining sessions, which were quick, frank, fruitful, and always ended up the same way: “We’d play poker.”

Charlie Nash joined the BC Power Commission in October 1945 and retired from BC Hydro in 1981. A UBC graduate in mechanical engineering, he had been a pilot in the RCAF and found work in the Commission’s Victoria headquarters shortly after his demobilization. In 1947 he was sent to Port Alberni.

I was sent there as district manager. Arnold McGilli-vray, who was the electrical superintendent in Port Alberni at the time, might rightfully have been expecting to become district manager, but the powers that be thought that they’d put a professional engineer into the job. The title didn’t mean much because I knew little about the utility business and Arnold knew it. But he was very magnanimous in saying “I know you haven’t had much experience, but I’m going to teach you everything I know.” And he did, and I respect him for that.

He introduced me to the whole community and taught me all sorts of things in the electric utility business, because being in charge of Port Alberni, you had to know everything. Well, you had to run everything. You had to run a diesel plant, you had to make an interconnection with our electricity supply company, had to design a new substation, had to talk with irate cus-tomers. It was exceedingly good training that gave the young engineers in the Power Commission a tremendously valuable start, because they didn’t pursue their careers down a narrow track.

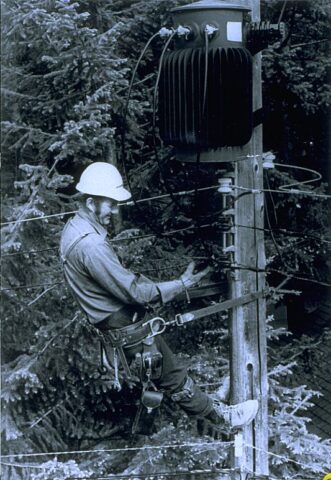

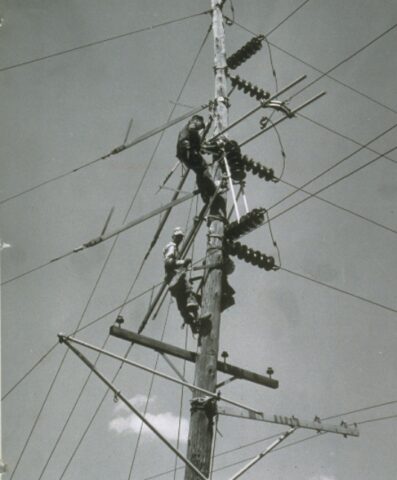

Charlie’s experience was typical. The district managers, often young men working long hours with a great deal of responsibility on their shoulders, were the vital link that held the BCPC operations together -especially in the early days. Typically, they would be involved in planning, management, administration, employee and public relations, and cost control, as well as power generation and distribution. It was not uncommon for some district managers to be out there climbing poles and doing the repairs. The ability of district managers to “do it all” served the Commission well in its rough-and-tumble early years and, some would say, benefited BC Hydro in its first days, too.

Back From The War

Phil Horton was a young boy during the Second World War, only 10 when the hostilities ended. He remembers taking the tram from Burnaby to visit his mother, Phyllis Horton, while she was working in the BC Electric mail room. Phyllis worked for BC Electric and BC Hydro from 1936 to 1965. During the war, BCE employees serving overseas were always very much on the minds of those at home, and Phil remembers conversations with his mother, who felt keenly the loss of her colleagues.

It was the old mailing department. I can remember putting the envelopes in the little machine. I probably shouldn’t have been doing it. I remember that I met some people who hadn’t gone to war yet and some who had. I remember a few who didn’t come back. I recall Mother being very sad at the end of the war because such-and-such a boy had died in the fighting. She would say to me, “Do you remember a Wally?” “Yes, I remember a Wally.” “He didn’t come back.” We felt very, very sad about it.

But, of course, many people did come back, and they were treated as if they had been employed. They could come back to their job and carry on. That didn’t always work out, because you know what a war does to some people. But they never lost their seniority with the company. And so it should be, too.

Many BCE men and women served Canada-both at home and abroad-during the war. Over two dozen employees died. Among them were William Douglas, only 20 when he enlisted, who died in an airplane training crash in Regina; William McLellan, killed fighting with the South Saskatchewan Regiment in Italy; G. R. Bing, of the gas division, and P. E. Brown, who worked for BCE in Chilliwack, both killed in action; H. O’B Hayward, who died while on active service in India; and Monte Tucker, of the BCE building maintenance staff, who was killed on the Italian front.

A beautiful roll of honour was commissioned by the company to honour the 621 mainland employees-both men and women-who served. (Many employees from Vancouver Island also served.) Phyllis Powell, of the BCE drafting department, worked for 45 hours on the lettering. Group of Seven artist A. J. Casson did the heraldry. Dorothy Pink, whose husband, BCE employee Walter Pink, died in the Far East, unveiled the roll of honour, which bears this moving passage:

I said to the man who stood at the gate of the year: “Give me a light that I may tread safely into the unknown.” And he replied, “Go out into the darkness and put your hand into the hand of God. That shall be to you better than light and safer than the known way.”

Despite the sadness of loss, BCE gained a new energy after the war, fuelled by the influx of men and women returning from the war effort. In 1945 alone, 322 BC Electric employees returned to the company to claim old jobs or start on new ones after serving in the armed forces; another 246 veterans found work with the company.

Jim MacCarthy came out of the Air Force and returned home to complete his last year of agriculture at UBC in 1946 and take a job with BC Electric. Jim remained with BCE and BC Hydro, working in many capacities, for almost 40 years. He remembers having many options after he finished university.

When I graduated, jobs were easy to come by. It was right after the war and we graduates had a choice of a number of jobs. I had been accepted into medical school at McGill University, but BC Electric’s offer of a job was appealing and I had a romance going, so I thought I’d work for a year before going to Montreal. BCE was a highly regarded company within the community. There was great leadership from people like Harry Purdy, Bruce Robertson, and, of course, Dal Grauer. He epitomized what BCE was all about.

Bill Duncan served in the Navy from 1942 to 1945. Before the war, he had worked Consolidated Truck Lines, which was owned by the BCE subsidiary BC Motor Transportation. Bill says that his war experiences changed him and better prepared him for the workplace.

What I learned during the war was that there was no point in getting excited about things. Some people think everything is a calamity, that there are no small events in life. A calamity to me is when your house goes up in smoke. Most people who know me say I’m pretty laid-back. I don’t know if that’s because of the war or not, but I did have enough experience under shellfire to realize there’s not much worse that can happen. It was good to have experienced it and come back whole. So many didn’t come back or not whole, psychologically or physically. Anyhow, I came back. And in those days, when you served King George, your job was waiting for you back home.

Don Davis says that when he got back to his desk in Victoria, “the fellow who had taken my job was so mad he went to Vancouver and took the first job there.” Don remembers how returning vets brought back with them some of their military ways. “Ted Fox from public relations had also been in the Navy. We used to see each other in the office and flash each other signals.”

After serving overseas, Bill Sharlow joined BCE’s gas department as a labourer in 1945. He retired in 1981. Bill was planning to work in the mines in Nelson, but when he stopped off in Vancouver he decided to stay and look for work.

I was waiting for a streetcar one day at the old office on Carrall Street. While I was waiting, one of the fellows said, “Why don’t you try the BC Electric? They’re hiring.” I had never thought about that, but I went in while I was waiting for this tram to come in. Bob Middleton was the employment man at that time, and he said, “We’ve got two jobs-in the gas department or the track department. They’re both labouring jobs, 68 cents an hour. The track department is mostly night work, because they are re-laying tracks.” So I said, “I’ll take gas,” because I’d had enough night work in the army.

They were putting a new 12-inch main down Main Street going up to Sixth and Quebec. They didn’t teach us very much when we started off. They’d give you a 12-foot piece of ditch and say, “You dig here.” All of the mains were dug by hand; they never had any mechanical equipment on that job. I was used to hard work -I’d dug ditches all over-so that was nothing to me.

Bob Mounce was another veteran who came home to a job with the company in 1945. He retired from BC Hydro in 1980. Bob found work on Vancouver Island at BC Electric’s Brentwood steamworks, the peaking plant near Victoria.

Brentwood was originally designed as an auxiliary plant to Jordan River and Goldstream. During the second war it got to be on 24-hour demand because of the shipbuilding. My brother was working there; he told Tom Walker, the superintendent at the time, that I’d be looking for work.

The steam plant was a 600-kW machine, the only one on the Island of any consequence. When the John Hart development power became available, the rates were good. There were all these little steam plants that burned hog fuel that shut down. I remember that they didn’t have modern scrubbers in the stacks and so they sent up lots of smoke and fly ash.

They’d rebuilt Brentwood in 1942. The original two units had six steam boilers feeding them, superheated, oil-fired. They were converted to coal during the war when oil was hard to get. The new plant used both oil and coal, whichever was available. They burnt the coal in suspension in the middle of the furnace; it was pulverized to dust and blown in. It worked alright except the coal had a lot of slag in it. It was sucked out into a hopper, but sometimes it was a big solid mass of slag. I know the plant used to heat up the end of Brentwood Bay by a few degrees-the fish were a lot bigger up near the plant wharf.

BC Electric’s Bridge River Era

In many ways the Second World War was a catalyst in BC-particularly its urban areas- bringing a wide range of industrial activity and almost full employment. After the First World War a generation earlier, people were simply grateful that four years of destructive near-stalemate were over. Now, there was a distinct feeling of hope and energy in the air. Spurred by wartime production, the economy was moving again, and BC Electric was one of the most prominent companies, hiring new employees and undertaking new projects. Almost everyone who worked for the company immediately after the War remembers the feeling of optimism.

The BC Electric Company office employee’s picnic at Bowen Island, 1950. From left: Anne Coroliuc, Betty Grant, Pat Jones, Merlene Rickert, Maisie Pinchin, W. McGeorge, Joanna Zacharias, Thora Purchase.

During the Depression and the Second World War, BCE had managed to maintain its existing operations, trying to get the most out of the infrastructure. Now, the company confidently made plans to meet the needs of a burgeoning and distinctly modern BC population, As the war effort in Europe drew to a close, BCE president W.G. Murrin announced a $50-million post-war strategic plan to dramatically expand operations.

For BC Electric, the period between the end of the war and the 1960’s was defined by the company’s highly respected president, Dal Grauer, who succeeded W.G. Murrin, It began with his appointment in 1946 and ended, with sad irony in the minds of most employees, on the day of his funeral in 1961.

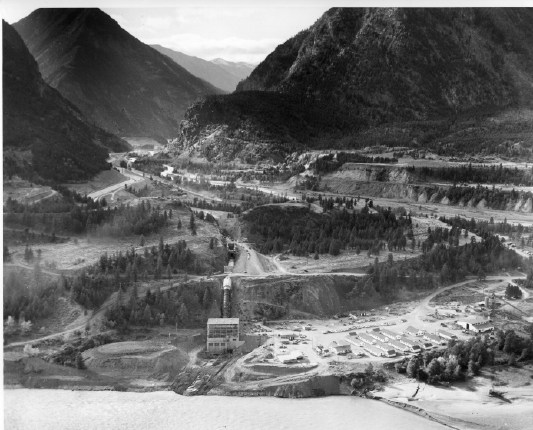

This was the Bridge River era. BCE restarted the huge project immediately after the war, and the final phases of construction were completed in 1960. By then, various interests cast their eyes north and east towards the Peace and Columbia Rivers and their tremendous generation potential. Service to customers greatly improved during this era, and new relationships were forged with them. The much-admired new BCE building in downtown Vancouver, which opened in April 1957, represented both a headquarters and a symbol of technological and business prowess.

But important parts of the company’s history were also left behind forever during these years. The legendary interurban railway system was decommissioned. The inevitable transition from “Rails to Rubber” was completed. In the Lower Mainland manufactured gas was replaced by natural gas and in the Fraser Valley gas arrived for the first time.

BC Electric changed a lot during this decade and a half: the company grew, its operations expanded, and the face of its workforce evolved. But as the 1960’s approached, no one at BCE could predict the tremendous social and political changes the decade would bring–changes that would spell the end of the venerable company as it had come to be known.

Power to The People: The BC Power Commission

After the Second World War, one of the biggest obstacles to growth in British Columbia was power-or the lack of it. Outside Victoria and Vancouver, countless communities were scattered over a vast, rugged territory. To fulfil BC’s potential, these smaller cities, towns, villages, and even individual ranches and homesteads needed the services enjoyed by the majority of the population in major centres. Numerous communities in BC did get power from small diesel and hydroelectric plants. Some of these tiny utilities were run by the local municipality. Others were privately owned and were often kept going with old-and sometimes unpredictable-machinery held together by all manner of materials and techniques.

The Nanaimo office secretaries in 1960. Form left: Fran Fielding, Ruth Komarnick, Margaret Steel, Janet Norby, Nel Williams, Elsie Steel. In 1943, even before the war ended, the provincial Public Utilities Commission put a rural electrification committee to work investigating ways to bring electric power services to more BC residents. At the time, there were just over 206,000 electricity customers in the province and about 75 percent of them were served by BC Electric. By 1945, the provincial government was ready to begin its drive to bring “power to the people.”

With the passage of the Electric Power Act in the legislature in 1945 by Premier John Hart, the British Columbia Power Commission (BCPC) was created. The Commission’s task was twofold. First, it would meld the existing hodgepodge of generation and distribution facilities spread across the province-and outside BC Electric’s territory-into one system. Second, it would extend service to many communities that didn’t have power at all. The goal was to spur population growth and industrialization in BC. In July, the Commission acquired its first utility, the Nanaimo Duncan Utilities (NDU) on Vancouver Island. Fifteen years later, the Power Commission had added more than 200 communities to its system.

The Commission wasn’t nearly the size of BC Electric, but that made no difference to company morale. The BCPC always remained BCE’s poorer cousin, right up to the time when the two organizations merged in the early 1960’s to create the new BC Hydro. But without the dedication of the BCPC’s employees, the province’s development would have been slowed and BC Hydro today would be a very different organization.